Location:

RM Sotheby's, Hershey, 2017

Owner: Thomas F. Derro | Carlisle, Massachusetts

Prologue:

The Silver Arrow is the car on which I conceived and built 12cylinders—even the livery of the 12cylinders logo uses the two-tone graphite and red trim of the two sister Silver Arrow cars remaining. Tracking down this car, Car No. 1 of the five originally built, became nothing short of my raison d'être.

We first saw Car No. 1 in 2007, where I gathered a few insubstantial photos. The next ten years of hope brought no further sightings until the car headed to auction in Hershey with the Thomas F. Derro collection. At the time, I worked at a federal financial corporation in Arlington on a business case for a major tech transformation. I took a rare day off to head north and photograph the auction cars, almost singularly for this Silver Arrow. As a bonus, the collection included Duesenberg J-519, the d'Ieteren Frères cabriolet, which we'd seen once before in 2006. I had longed to photograph both cars, and finding them side by side in the same collection proved serendipitous, if not strictly practical.

Shifting my focus into Pierce-Arrow, all work leads to the Silver Arrow, quite simply one of the most significant automobiles of the 20th century. Full stop. My objective is to provide the best profile possible, illuminating the design for its leading-edge merit while discussing the historical qualities that too few in the automotive world seem to remember.

What we see here is a rare (and perhaps the first) combination of fastback profile and fully concealed envelope-style streamlining. With very little precedent, and with lasting influence, the Silver Arrow proposed a clever design philosophy that brought together the most advanced concepts of the decade. To prove its technical strength, under the bonnet is a development of the Pierce-Arrow V-12 that David Abbott Jenkins drove to endurance speed record success, a couple years before besting his efforts with the Duesenberg Mormon Meteor J-557 under Lycoming and Curtiss power.

A ground-breaking aerodynamic design with the technical quality of a land speed record car, I feel the Silver Arrow does not often receive its deserved recognition. Part of the reason is Pierce-Arrow's imminent demise and the relative eccentricity of the Silver Arrow compared to the more conservative Pierce-Arrow production catalogue. So the Silver Arrow falls into a void between esoteric art piece and experimental exercise, much appreciated by small pockets of enthusiasts, but not often a first-hand response when folks compile lists of proverbial greats.

- - - - - - - - - -

► Image Source: Nikon D750 (24.3 MP)

References:

- Ralston, Marc. "Pierce-Arrow" A.S. Barnes & Co., Inc., San Diego, CA. 1980, page 177-178

- Automobile Quarterly, Volume 28, Number 4, Fourth Quarter 1990, "The Last Years of Luxury" by John C. Meyer III, The Kutztown Publishing Company, Inc., Kutztown, PA, page 92-94

- Automobile Quarterly's World of Cars, Kutztown Publishing Co., Kutztown, PA, 1971, page 217-218; adapted from "Pierce-Arrow: An American Aristocrat" by Maurice D. Hendry, Volume VI, Number 3

- RM Sotheby's: The 2017 Hershey auction description, representing the Thomas F. Derro collection.

- Autoweek: "1932 Maybach Zeppelin Streamlined Limo," by Michael Lamm, Autoweek, June 9, 1997, page 23

- HowStuffWorks: A very nice piece on the design process.

The original Silver Arrow show car represents the automotive ideal as conceived by a company whose technical standards were both excessive and unique. No other marque had dared to industrialize cast aluminum bodies. The entire industry followed Pierce-Arrow into six-cylinder development. Perhaps no marque built a more reliable car so early in the automobile's collective development than Pierce-Arrow. And yet the company's stalwart attitude bred stagnation. By the 1930s, advances in style meant more to the consumer than Pierce-Arrow's reputation could overcome. The Art Deco period had arrived. So had austerity, sulking on the leaded wings of the Great Depression. Once the best, Pierce-Arrow found themselves under heavy domestic competition from Cadillac, Marmon, and Packard. Sales and survival in the luxury segment depended on creating a product that fit the new-age paradigm and justified the expense, an alchemical challenge Pierce-Arrow seemed unprepared to meet.

Phillip Wright and the Silver Arrow

Enter Phillip O. Wright. With his eye for sultry lines and laudable credits at General Motors and Cord, Wright brings in his back pocket a design that merges two pivotal trends within one platform. First, the fastback profile is one of the earliest commercially viable exercises of its kind. The concept stems from Paul Jaray's studies, but had not yet been brought to market in a consumer package. Originally termed "beetle-back" by the factory, this mainstay of streamlined design precedes French exercises from Bugatti, Delage, Peugeot, and Talbot-Lago from anywhere between two and five years. The nearest relation is the Studebaker Commander Land Cruiser Sedan of 1934, also penned by Wright. Produced at the close of Studebaker's ownership, each of the five Silver Arrow show cars was built by hand at Studebaker's experimental body division, so the Silver Arrow show car design translates to both Pierce-Arrow and Studebaker production cars.

Silver Arrow Precedent in the Maybach DS8 Typ Zeppelin Stromlinien

More significant than the fastback sedan profile, Wright creates one of the first "ala spessa" design exercises, eliminating separate running gear and fenders by merging them into closed quarter panels. The precedent for this plan is the Maybach DS8 Typ Zeppelin Stromlinien, built by Spohn in 1932. That car, destroyed during allied raids on Friedrichshafen, is the only antecedent to the Silver Arrow's general plan. The two exercises debuted six months apart. Not simply the fastback roofline, a slippery, aerodynamically correct attack through the fascia conceals the chassis within an undulating scoop, channeling air out along the edges of the cabin. Spare wheels, instead of sitting exposed on running boards, fit behind hinged panels on the flanks. The German design terms this aerodynamic fascia an envelope style, which proves far less popular in period than Jaray's fastback.

For its part, the Maybach would most closely predict the Avions Voisin C28 Aerosport of 1935, the Chrysler Airflow of 1934, and arguably the Tatra T87 of 1937, (which is admittedly a different animal). In the history books, these three automobiles draw regard as experimental exercises, whereas European fastback designs quickly became the premier fashion models of the high classic era. That the Silver Arrow combines these two design trends in one platform is remarkable; it is the first, and perhaps one of the only automobiles to do so.

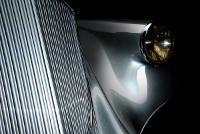

A moment of conjecture: While the Maybach similarity is unmistakable, what appears revolutionary for Pierce-Arrow may be more simply evolutionary. Pierce-Arrow first integrated headlamps into the front fenders in 1914. For the next two decades, that design feature would define Pierce-Arrow cars. Apart from the cast aluminum construction process, which itself is not immediately visible, Pierce-Arrow relied on no other style measure than integrated headlamps, even as cast aluminum bodies became infeasible and the company shifted to conventional body-on-frame assembly. But in that same regard, using the integrated lamps as a starting point and creating a fluid line extending back into the body shoulders seems a simple way to create a modern, streamlined design. And no other auto manufacturer would be in position to pen that stroke. Pierce-Arrow had patented the integrated headlamp design, so no other would be apt to use as its starting point an integrated fender—at least, not without aping what had been a Pierce-Arrow staple for 19 years.

From this perspective, the Maybach precedent may not have been the only seed for the concept. Wright had submitted his design to GM prior to joining Pierce-Arrow, and the Spohn-built Maybach is surrounded in mystery regarding who influenced its design. Paul Jaray himself had been a nearby resident, though his telltale style is not so prevalent.

So what can we conclude? Automotive development just tended to evolve this way, through comparable ideas gestating simultaneously on different continents. The race to innovate—dating back to the inception of the internal combustion motor, the four-wheel Système Panhard, dual overhead cam multi-valve technology, and the front-wheel drivetrain—always involved different people from different backgrounds who fostered similar ideas. Maybach and Pierce-Arrow were merely the first to demonstrate this set of aerodynamic advances, blending them in different quantities of American and European design trends.

Trickling from the World's Fair to Crazy Water

As we know, the Pierce-Arrow Silver Arrow production cars that followed reverted to conventional fenders and running gear. Phillip Wright's design proved exorbitantly expensive, and while the five show cars sold to private owners, these sales did not represent Pierce-Arrow's typically conservative customer base. Our car, chassis #2575015, is the first of the five Silver Arrows built. In turn, Car No. 1 debuted at the New York Auto Show in January of 1933, four months ahead of the famous World's Fair exposition in Chicago. RM Sotheby's cites the first purchaser as, "M.C. Hudson, the San Francisco distributor for Crazy Water, the famous health-giving mineral water bottled in Texas since 1881. Liveried with Crazy Water logos on the doors, the Pierce served to promote the famous miracle cure throughout California."

Crazy Enough: The Crazy Water brand lives today, but in period evoked a miracle-cure campaign. That an eccentric executive would use the Silver Arrow as an advertising device speaks to the design's own eccentricity, to say nothing of the public's general lack of sense of what to do with it. Even more can be said about the Chrysler Airflow that is about to fail miserably in 1934, (and the Pontiac Aztec of 2001 whose design the public still cannot seem to recognize in nearly every crossover SUV available in the contemporary market). The bottom line, Pierce-Arrow found no demand for the Silver Arrow, and could not produce it in its true form even if the demand were present.

Silver Arrow Performance Proven in Land Speed Records

We should also point out that the might of the Silver Arrow is not purely artistic. Pierce-Arrow 8-cylinder and 12-cylinder motors adopted hydraulic tappet valves in 1932, an innovation shared with the Cadillac Series 452 V-16 of 1930. This advance provided zero valve clearance for greater efficiency and smoother operation, and became the automotive industry standard for a century. Other 1932 advances ripe for the early 1933 Silver Arrow release included eight-point engine mount bushings, adjustable shock absorbers, and power-assisted brakes.

The Pierce-Arrow V-12 found in the Silver Arrow is also the descendant of 1932's land speed record cars. Automobile Quarterly recounts, "In September of 1932, with a basically standard car which had already seen 33,000 miles in the hands of test drivers, Ab [Jenkins] started driving the salt flats, without relief as was his custom. Twenty-four hours later he had piled up 2,710 miles at a 112.91 mph average—without any trouble. Fenders, windscreen and road equipment were then returned to the car, and it was immediately driven another 2,000 miles across the continent to Buffalo, without a major adjustment of any kind. This run was followed by two more in 1933 and 1934."

Jenkins' endurance record topped out at an average of 127 mph over 3,053.3 miles. Pierce-Arrow broke 14 Federation Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) records, only to be bested by Jenkins in later aircraft-powered Duesenberg attempts. The level of quality and performance built into the Pierce-Arrow V-12 might have been matched by those with similar diligence, but few tested to the same extreme. Of their own motors, Pierce-Arrow wrote, "After two hundred and fifty hours (a continuous two weeks of day and night running), they developed no major trouble." And as if to prove the veracity of the claim, the car Jenkins used for his second 1932 record attempt had already spent 156 hours on the dynamometer at 4,000 rpm before heading back to the salt flats.

In its promotional literature for the Silver Arrow, Pierce-Arrow claimed, "Here is a car which weighs 5,100 lbs. and is ready to do 115 mph with a 175 hp motor!" And the formula proves true, (except the original Silver Arrow actually weighs more than 5,700 lbs). Still, the technical quality, proven speed and endurance, and advanced aerodynamics created a package of equal opulence and efficiency. The Silver Arrow show car is not merely a stunning design exercise, but a truly great car simply by virtue of being a Pierce-Arrow.

Motor: 7,570 cc (462 cubic inch) 80° V-12, cast-iron block | 88.9 mm x 101.6 mm (3½" x 4") | 6.1:1 compression

Automobile Quarterly surmises, "The known serial numbers of the Silver Arrow engines (360001, 360003, 360005, and 360007) would indicate a special run that included the Ab Jenkins specials." This reference draws a tighter connection between the Silver Arrow V-12 and the V-12 record cars. This Silver Arrow, the first built, uses engine #360001.

Valvetrain: L-head, 2 valves per cylinder, with self-adjusting hydraulic tappets developed and patented by Carl Voorhies

Aspiration: Stromberg dual downdraft carburetor

Power: 175 bhp @ 3,400 rpm

Drivetrain: 3-speed gearbox, rear-wheel drive

Front Suspension: solid axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs, friction dampers

Rear Suspension: live axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs, friction dampers

Architecture: steel ladder frame chassis with all-steel body

Pierce-Arrow originally conceived a rear-motor platform, but due to complexity and schedule demands opted for a standard Model 1236 chassis.

Kerb Weight: 2,598.6 kg (5,729 lbs)

Wheelbase: 3,530.6 mm (139 inches), based on the 139-inch Model 1236 production chassis

Top Speed: 185 km/h (115 mph)

Etymology:

The Silver Arrow show car became the first in a long while to echo the marque's tradition of early Arrow and Great Arrow cars, a play on old terms not seen since the early otts. As of 1908, the marque hyphenated its name, "Pierce-Arrow," and despatched with similar nomenclature in favor of ever-cryptic model numbers with alphanumeric appendices. To simply name its show car "Silver Arrow" made a statement. Pierce-Arrow hinted at a return to form, when the marque was among the best in the world, and also blatantly declared that this car would be a modern icon of that greatness, which of course it is. If it were a production car, the Silver Arrow would be labeled a 1933 Model 1236 Silver Arrow.

Figures:

Pierce-Arrow built five Silver Arrow show cars at Studebaker's experimental body division in the autumn of 1932, completing this car, the first, in time for the New York Auto Show on January 1, 1933. They readied the second car for delivery back to Buffalo in mid-January, and the third for delivery to Chicago by the end of January, where it would later appear at the World's Fair. The final two cars returned to Buffalo in mid-February. With Studebaker's help, Pierce-Arrow completed the entire Silver Arrow project in under four months, with this, the debut car, ready to go in about three. Given the marque's obsession with quality, meeting these deadlines required true devotion among the craftsmen responsible. Today, three of the five Silver Arrow cars remain; these are distinct from the later production series, which could not carry forward the same aerodynamic body or cabin appointments for want of extreme cost. In his work, Marc Ralston names three surviving Silver Arrows as cars 003, 005, and 007, though RM Sotheby's cites this car as body No. 1. Ralston also mentions a fourth surviving car that was rebodied as a roadster and became part of the Harrah collection. Suffice to say, we're looking at the New York Auto Show car in this profile, the first of five built and one of three complete Silver Arrow cars known to survive.

Value:

Pierce-Arrow sold the five Silver Arrow cars for $10,000 each, which was both an extreme cost at the time and far less than their actual value. These five sales did not come easily, either. Remarkable though it may be, the Silver Arrow did not align with Pierce-Arrow's typically conservative clientele, and its predictive styling would have seemed rather experimental to most consumers besides. Pierce-Arrow were never a marque that catered to eccentrics, essentially the diametric contradiction to Jacques Saoutchik. Developing a car so bold reminds us today of Pierce-Arrow's exceptional class and competence, and more broadly proves how exceptional American automobiles were in the classic era.

In 2017, this Silver Arrow sold at RM Sotheby's Hershey auction for $2,310,000.

Seminal Design: Early Influence of the Fully Enclosed Fascia

Of all Art Deco exercises, American or Continental, the Silver Arrow is among the earliest and most confidently modern. Phillip Wright's design combines enclosed envelope-style fascia, seen only on the Maybach DS8 Typ Zeppelin Stromlinien to date, with a fastback tail that will become the high art trend throughout the remainder of the decade. French coachbuilders will soon seduce with flowing lines. Italians will land aircraft fabrication techniques on four wheels for lightweight finesse. And Americans, Germans, and Hungarians alike will curve steel in favor of aerodynamic efficiency, often patterning automotive shape on the prestige of railway advances. But before all others appear on scene, the Silver Arrow offers a menu of forthcoming design concepts in one experimental package. Not to claim absolute precedent, which is never simple in automotive history, it is this combination of future trends that makes the Silver Arrow particularly significant.

In 1932, Wright would have seen the Maybach Stromlinien, which completely enfolds the front wheels, creating nacelles that extend up to the A-pillars in a strangely streamlined tank profile with slab-side flanks. The headlamps are embedded within the nacelles with a stabilizer bar drawn between as if were a conventional light bar, though the nacelles conceal its mounting points. Two different headlamp configurations appear on the Maybach, one more popularly shown with rounded lamps, and one with protruding lamps that were also faired in. Look up photographs and the difference is easy to spot; the two-tone paint also reverses on each variation.

But at Pierce-Arrow, Wright begins with head start. Pierce-Arrow had patented integrated headlamps in 1914, one of few stylistic trends the marque had ever bothered to lead, but one that in 1932 provides an excellent starting point for a streamlining exercise. By simply extending the headlamps back alongside the bonnet, Wright creates the same nacelle effect. He then softens the brutality of the slab-side profile with a step-down curve over the side-mount spares.

Original Counterpoint: Wright's GM Car-of-the-Future Design

Between his time at Cord in 1931 and his escapade at Pierce-Arrow, Wright stopped at GM for a spell. At GM, he submitted a design for Harley Earl's car-of-the-future brief, but GM declined to model the design. Automobile Quarterly suggests that, when Roy S. Faulkner pulled Wright over to Pierce-Arrow, he asked Wright to re-work the car-of-the-future design penned for GM. This interaction suggests a more original tack in the Silver Arrow form, perhaps even less dependent on the Maybach precedent. Wright himself also recalls some friction with Studebaker's Chief Engineer, Jimmy Hughes, who changed design elements in early mocks. Those changes led to Hughes' quick exit and creative reigns handed solely to Wright, though some sources still contend the final car incorporates elements not of Wright's own mind. (Automobile Quarterly notes that it was Hughes who reduced the wheelbase to 139 inches, a good decision, and he may have added the bow tie rear windows.)

But these sources may have misconstrued the timing of others' intervention, when the designs were changed, whereas those changes were recovered by Wright for the final build. The team worked extraordinarily fast to design and build these show cars, and different sources spoke to different men within the team (on different sides of the friction), so confusion over the exact process is somewhat understandable.

Arrow Theme: Design Elements that Reinforce the Silver Arrow Concept

Both Maybach and Pierce-Arrow designs result in deeply sculpted soffits between the nacelles and bonnet, but differ greatly in their attack. The Maybach fascia is a giant scoop enunciated by a concave grille, with seamless coachwork and completely enclosed fenders. The Pierce-Arrow is a shovel-nose, following the shield-shape of the grille to a chin deep below the guard (11). Panel seams run up the soffits and form the lower bonnet edges (3, 4); they join the outer fender panels in sculpted covers around the front chassis rails (11), which also serve as mounts for the front guard. The curves of the deep vee then draw into wings out around the tyres at a conventional fender height.

In pieces, the work looks complex, but when we take all of these directed cues together, we find a remarkable theme: The vee windscreen points to the bonnet, which is scalloped and points directly to the mascot. The mascot archer aims ahead at the wind. The base of the mascot forms a scallop that points down to the grille. The shield-shape grille tapers down toward another fine chrome scallop, which points at yet another chrome accent along the leading edge of the chin with one final scallop pointing forward. The shield at the center of the guard also mimics the grille and ends in a fine point. Every cue leads the eye forward from one sharp point to the next; it is the ultimate thematic expression of the Arrow theme that began merely in name back in 1903.

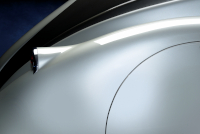

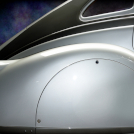

Incredible Tale: The Combination of Fastback and Tapertail Style on the Silver Arrow

As complex as the fascia may be, the tail is equally magnificent. Separate skirted fenders extend from the body, which seems conventional at first, but the effect is cheeky. In profile, the Silver Arrow looks bulbous, not unlike the Maybach. But in perspective we see that the body tapers quite dramatically around the rear quarters, which lessens the bulk and lightens the stance. The body is not only a fastback, but a tapertail as well, drawing a series of complex panels to a narrow bow with soffits that complement the fascia. The moulded panels that work so well with two-tone paint also act as buttresses, providing rigidity to the flowing body. Faired-in tail lights do little to disrupt the lines, and the rear guard augments the shape by curving around each cascading section. The whole composition squeezes boot space, with a hatch only a wide as the central section between the buttresses, function that follows elegant form with its tongue lolling out. Yet where function may be lost altogether, the curious bow tie window above is a measure of practical fantasy. While a chance to add yet more contrast paint to a vee-shaped design element, the medieval visor also provides much-needed headroom for rear seat passengers.

Ingress Anomalies: Designing the Standard Pierce-Arrow Chassis as a Step-in Platform

While we laud the enclosure of running gear and side-mount spares behind hinged body panels, the Silver Arrow is still a production Model 1236 underneath. In 1932, Wright wants to build a rear-motor, open platform car, a plan that would incorporate innovations comparable to Stout and Tatra. Of course the imminent delivery date means using a production platform, which in turn means that the envelope body needs to somehow join the conventional cabin. So, where the curved suicide doors meet the back edge of the spares compartment, the doors are over one foot thick. The traditional width of the running gear needs to be consumed somehow.

Despite the bulk, Wright maintains a more seamless ingress-egress plan not unlike an open-platform car, departing from the traditional step-up platform typical of body-on-frame manufacture. For the rear compartment, the taper-tail design mitigates this problem as the body draws tighter to the cabin. Note also that the doors open into each other, toward the B-pillars, and that the handles are recessed.

Sharp Anomalies: Faired-in Tail Lights

Though small, the tail light design (possibly a Hughes device) is remarkable for its adherence to the overall theme. The tail light housings are both vee'd and scalloped, yet still sit flush on the curved fenders. These units will appear on subsequent Pierce-Arrow production models henceforth. On the Silver Arrow's right rear fender, the effect is particularly smooth. On the left, the housing includes a light on top to illuminate a rearward-facing "Pierce 12" mascot. These tail light fixtures very nicely augment the split-vee bow tie rear window. Also note that the shoulder-line moulding begins with a fine point at the headlamps, extending back in a long scallop to the front doors, paired by the scallop pattern on the bonnet. The hood (roof) above echoes the same treatment with a short scallop at the top edge of the vee windscreen. Details that fit within broader themes create harmony in spite of complexity. Every element, top to bottom, has an echo.

Last Updated: Mar 26, 2025