Location:

Moda Miami, 2024

Elegance at Hershey, 2014

Owner: Harry Yeaggy | Cincinnati, Ohio

Prologue:

A considerable privilege, J-557 has crossed our path twice, and while I feel remiss in not managing an illustration of this incredible motor, profiling this car feels rewarding enough. Just the concept that one can visit a public event and pour over the design feels like a small coup, as if spending any time near the vehicle requires its own admission fee.

Simultaneously art and artefact, J-557 succeeds in the practical application of speed through an extraordinary collection of aerodynamic shapes spread across a grand chassis. The Duesenberg Special should be one of the world's foremost classic automobiles, not merely an American great, because it codifies the Model J's supremacy through land speed records. I suspect an alien perspective would be to dismiss J-557 as something of an extravagant hot rod (which it is). But this Duesenberg is the same that bested a British purpose-built record car at Bonneville, then returned to common road use afterward.

We make noise about those fantastic European sports cars that won races then drove off through the mountains back to their domestic haunts. J-557 is an American corollary. One would never drive home Eyston's Speed of the Wind record car, but Ab Jenkins enjoyed J-557 for decades after his Bonneville record campaign. The Model J was simply designed and built differently than the rest—a class perhaps shared only with Hispano-Suiza—and J-557 proved this point particularly when it ran at Bonneville under Lycoming power.

So please enjoy the spectacle, however static it may be. The inaugural ModaMiami provided a brilliant stage for a new set of illustrations, though I still quite like the original set from ten years prior.

Back then, I'd brought along a good friend and experienced urbanex (urban exploration) photographer to the Elegance at Hershey. Glitzy chrome and a garden party, Hershey was the opposite of his usual shooting environment. I made do with my old kit, and yet the results became somewhat important to me in terms of learning how to piece together a cohesive set.

All the same, I wouldn't tire of shooting more curves and chrome and quarters if we are so privileged to see J-557 again. There are plenty of details yet to capture.

- - - - - - - - - -

► Image Source 1-25: Nikon D750 (24.3 MP) photographed in 2024 | Image Source 26-40: Nikon D200 (10.2 MP) photographed in 2014

References:

- Automobile Quarterly, Volume 30, Number 4, Summer 1992, "They Always Called Him Augie" by George Moore, The Kutztown Publishing Company, Inc., Kutztown, PA, page 20-21, 23

- Automobile Quarterly, Volume 30, Number 4, Summer 1992, "Chariots of the Gods: The Grandeur of the Model J" by Randy Ema, The Kutztown Publishing Company, Inc., Kutztown, PA, page 55

- The Truth About Cars: "Ab Jenkins and His Mormon Meteor, Part One" by Ronnie Schreiber, November 24, 2015. A lengthy historical presentation, few pieces will give so much information, let alone the period photos and paraphernalia.

- BANGshift: A nice story about Ab Jenkins and the speed record tractor campaign.

- Wikipedia: A decent piece on the Mormon Meteor.

Duesenberg J-557 was built by David Abbott Jenkins, Herbert Newport, and Augie Duesenberg to attempt land speed records. Under Duesenberg power, the trio succeeded in 1935 with a record averaging 135.47 mph over 24 hours, and a record averaging 152.145 mph over one hour. The team conducted all record attempts on the Bonneville Salt Flats, running a large, ten-mile ring. J-557 later became a more serious land speed record (LSR) car, but the intent of the original 1935 endurance runs (between August 6th and August 30th) was to bolster the Duesenberg brand image.

The business of Bonneville speed records being somewhat complicated, it becomes difficult to parse classes and records from a century ago. Beverly Rae Kimes' 1990 book, "The Classic Car," suggests that the 24-hour record would stand until 1961; but if true, then the claim would either pertain to some category of production car or to the record set in 1936 under Curtiss power.

Nevertheless, the vehicle depicted here is both the speed record Duesenberg Special run at Bonneville in 1935 under Lycoming power, and also the Mormon Meteor run at Bonneville in 1936 under Curtiss power. The Mormon Meteor name applies retroactively to the original special, prompted by Jenkins' christening of the Mormon Meteor when he exchanged the Lycoming unit for a Curtiss aero engine in 1936, which in turn became retroactively known as the Mormon Meteor II. But these are two versions of the same surviving car. Also note, even though we identify all Model Js by their engine numbers, this particular car has no chassis number, and is perhaps unique among Duesenbergs for it.

Impetus behind the land speed record attempt stems from Harold Ames, Duesenberg Vice President. Much like Pierce-Arrow, Duesenberg wished to garner an accolade to tout its product and boost sales, recapturing something of its past performance glory. For Pierce-Arrow, past glory translated to endurance trials, whereas Duesenberg remembered Indianapolis racing success and, way back in April of 1920, the radical twin-engined Duesenberg Tommy Milton Special that ran at Daytona Beach. A prototype special, that car cracked over 156 mph.

Driving for sister marque of the A-C-D empire, Ab Jenkins had recently run a supercharged Auburn 851 at Bonneville, as well as a stripped-down Pierce-Arrow with the new 462 cubic inch V-12 designed by Karl Wise. Augie Duesenberg had wanted to attempt the record for some years, as early as 1930, but he and Ames found corporate leadership at Cord unyielding. Jenkins' speed runs for Auburn loosened purse strings and provided Duesenberg with a ready driver. So Augie set to work on the Duesenberg Special, and Jenkins arranged for its procurement as a condition of his support.

David Abbott Jenkins and the Duesenberg Mormon Meteor Record Car

Duesenberg set out to own the record books for a modified chassis and drivetrain, particularly in the endurance categories. Sources often cite "Class B" as the record designation, though I find it hard to discern what the designation means relative to today's LSR parlance. A blown fuel streamliner (BFS), for example, fits the description of J-557, though it is far removed from the LSR monsters we know today.

As for the challenge, no other producer was so well positioned to hold this title as, at the time, no American car manufacturer produced a motor that approached half of the Model J's performance. The special prepared by Jenkins and Duesenberg improved on that margin of superiority, holding sway until the aero motors moved in. And yet Augie's experience developing heavy-duty high-performance machinery proved fundamental to the task, providing a strong enough platform to later compete against a British purpose-built speed record team.

But first, the production car: Stock Lycoming straight 8-cylinder motors yield about 265 bhp, whereas the modified unit in the original Duesenberg Special broaches 400. High-lift cams pushing a 7.5:1 compression ratio, massive updraft carburetors, new intake manifolds, and a centrifugal supercharger proved both powerful and reliable. Not to be exclusive to racing, Duesenberg later applied these modifications to numerous road-going Model Js.

The first test occurred on May 30, 1935 at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, an appropriate place to start considering Duesenberg's great success at Indy in the previous decade. Once at Bonneville, (Wendover, Utah), official tests ran long due to bearing issues, but ultimately proved successful with the one-hour and 24-hour records in hand. Considering that Duesenberg designed and developed the Model J's Lycoming straight 8-cylinder back in the late 1920s, laying claims to the world's fastest production car so many years later could knock the rust off anyone's perception of the marque. Job done for Duesenberg marketing. But of course translating that success to the bottom line still proved impossible in the Depression era.

Following the team's success in late 1935, Jenkins purchased the car from Duesenberg for $4,800, as agreed. He then replaced the modified Lycoming 8-cylinder with a Curtiss V-1570 Conqueror aero motor, giving birth to the Mormon Meteor.

This aero-transformation came about after George Eyston and John Cobb broke the Duesenberg Special's records in September of 1935 with their purpose-built Speed of the Wind. That British record car used a 21.25-litre Rolls-Royce Kestrel V-12.

At 1,570 cubic inches (25.727 litres), the Curtiss V-1570 vied with Rolls-Royce for supremacy in horsepower and operating efficiency, with both manufacturers using the Curtiss D-12 motor as a benchmark. Both developed the motors in the early 1930s from their original designs dating to the late 1920s, most notably by adding superchargers. The Kestrel, however, would see much broader real world application in the coming war.

Accounts differ as to whether the Conqueror motor that Ab Jenkins used developed a naturally aspirated 600 horsepower or a taller figure accounting for forced induction nearer 750. But in either case, fitting a motor almost four-times the size of the stock Duesenberg J to the Special's chassis is a spot of backshop engineering wizardry.

So in 1936, the Eyston/Cobb team battled the Jenkins/Stapp team. Initially, the British car took over the 24-hour and 48-hour speed records. The Mormon Meteor Duesenberg then reset the 12-hour record, but lost a driveshaft. John Cobb then reset Eyston's 24-hour record. After Jenkins' team repaired the Duesenberg, he and Stapp returned for a second run; they retook the 24-hour and 48-hour records, reclaiming those previously held in the car's dossier as J-557. Together, Jenkins and Stapp raised the 24-hour record to an average of 153.823 mph, and raised the 48-hour record to an average of 148.641 mph.

Through these 1936 speed battles, the team found that the weight of the Curtiss V-12 over-taxed the Model J chassis, causing strong understeer at speed. Not surprising, as the car is mainly a modified Model J. Thus, Jenkins attempted further speed record runs with a purpose-built car, also built by Duesenberg, and henceforth named the Mormon Meteor III.

With a purpose-built record car in hand, Ab Jenkins returned the Mormon Meteor to the road, reinstalling the original modified Lycoming J-557 unit, which effectively restored the car to its formative Duesenberg Special configuration. Along with his son Marvin, Ab would put more than 20,000 miles on the car in private use. Even after Jenkins' ownership, the car continued to receive regular care and frequent use, notably while the property of the Kershaw family, who owned J-557 from 1959 to 2004.

Ab Jenkins' specialty was endurance records. In addition to speed testing the Auburn and Pierce-Arrow at Bonneville, he completed over 40 cross-continental runs for sponsorship publicity. Surprisingly, Jenkins was not a proponent of wheel-to-wheel racing. Though he enjoyed the business of chasing records, he confined high-speed motoring to solitary endeavor, and according to most, maintained a nearly irreproachable driving record, never receiving a speeding ticket and only once merging car with obstacle. That incident occurred in 1951 during a high-speed run, when he crossed a water slick at 200 miles per hour.

Of the man's personality, the Mormon Meteor moniker gives a nod to Jenkins' affiliation with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. But beyond the obvious, Jenkins was a keen marketer. He understood the value of endorsements, and used his widely acknowledged good character to secure funding from all manner of companies over the course of his driving career. It was owing to this knack for sponsorship deals that Jenkins was able to manufacturer a driving career in the first place, (though he did serve a stint as the 24th mayor of Salt Lake City, Utah).

While all this automotive commotion happened, Jenkins also entered into a playful duel with performance motoring veteran Barney Oldfield, this time on tractors. Again, the impetus was advertising. In this case, tyre manufacturers wanted to prove to farmers the value of rubber tyres to replace traditional steel wheels. Firestone teamed with Oldfield, who began running high-speed demonstrations, topping 64 miles per hour. Meanwhile, Jenkins also teamed with Firestone for a tour of his own. On an Allis-Chalmers with specially designed tyres, Jenkins would prep for his automotive speed runs with a few open-air sprints on the tractor. He set a record of over 68 mph at Bonneville, comparing the experience to riding "a frightened bison."

Motor: 6,876 cc straight 8-cylinder, cast iron block and head | 95.3 mm x 120.7 mm | 7.5:1 compression

Valvetrain: DOHC, 4 valves per cylinder

Aspiration: dual two-barrel Stromberg UU3 updraft carburetors, centrifugal supercharger

AQ note, "One big problem involved fuel flow from Augie's special dual-carbureted supercharger. Finally he conceived and built a ram's horn crossover manifold out of tubing and the Special's horsepower shot up, ultimately to 400 bhp at 5,000 rpm. In addition to the manifold, the Special had a larger impeller, special cams, sprockets and plugs, and a pressurizing fuel tank." Once performance retrofitting got underway, the ram's horn manifold design became a standout feature of the supercharged J.

Power: 400 bhp at 5,000 rpm

Drivetrain: Warner Hy-Flex 3-speed manual gearbox, rear-wheel drive

The Duesenberg Special uses a 3:1 gear ratio, lower than standard Model J options in deference to greater endurance.

Front Suspension: solid axle with semi-elliptic leafsprings and hydraulic shock abosorbers

Rear Suspension: live axle with semi-elliptic leafsprings and hydraulic shock absorbers

Architecture: steel ladder-frame chassis with aluminum coachwork by Herbert Newport

To make the car lower, Augie Duesenberg dropped the front axle to the chassis and chose 18-inch wheels instead of the traditional 19-inch complement.

Kerb Weight: 2,177 kg (4,800 lbs)

Wheelbase: 3,620 mm (142.5 inches)

Top Speed: about 155 mph

Etymology:

The 'S' designation applies retroactively to the Model J, denoting the addition of a supercharger, though it does not encapsulate all the modifications made to this particular car.

Duesenberg originally named this car the Duesenberg Special. After David Abbott Jenkins purchased the car and swapped in a Curtiss Conqueror V-12 motor, he christened the speedster as the 'Mormon Meteor' following a publicity drive to name the car published in the Salt Lake City Deseret News. Finding the stock chassis ill-fit for the heft of the Curtiss motor, Jenkins replaced the Lycoming unit and toured the car extensively across the country.

But this nomenclature is somewhat retroactive in its application. Looking rearward, the Lycoming-powered Duesenberg Special is the same configuration as what we call the Mormon Meteor today, which can be said to exist both originally (as conceived by Duesenberg) and after Jenkins finished his personal speed runs with the Curtiss-powered variant in 1936-37.

Retroactively, the car Jenkins named the Mormon Meteor we now consider the Mormon Meteor II, mainly for the sake of continuity, which came and went as it is only a variant of this same car with Curtiss power. The Mormon Meteor III is a second, and ultimate Duesenberg speed record car built on a different chassis.

The 'J-557' designation is the motor number, one of two originally prepared for land speed record attempts; it is the same unit that ran during those first speed record runs for Duesenberg in 1935, and the same unit that toured so many miles through the heart of the continent after Ab Jenkins purchased the car for his personal use.

Figures:

A now-defunct registry listed more than 460 Model J Duesenbergs known to circulate in public. The factory originally produced perhaps close to 490 chassis; pundits often settle on the figure of 481. Of all Model J Duesies, the Mormon Meteor is peculiar in that it never received a chassis number. Furthermore, the car was built by Augie Duesenberg himself, along with David Abbott Jenkins. The body by Herbert Newport is also unique, and certainly the car's speed record history is unique. There is no other Duesenberg like this one, and really no other car quite like it either.

Value:

Bought for over $4 million in 2004, it's impossible to say what the Mormon Meteor would sell for today.

Record Cars: Reversing Expectations of LSR Monstrosity

Some may think the overall composition is that of a monster speedster, but the opposite perspective is to think of J-557 as a cut-down, production-based land speed record car. In the main, LSR designs really are monstrous—long projectiles on hard chassis, clad by medieval aerodynamic concepts. And yet by comparison this Duesenberg Model J brings that monstrosity down to a roadworthy scale.

Designer Herb Newport needed an appealing shape because Duesenberg intended for the car to capture public interest, so in many ways the speedster carries the look of speed even as the record attempts did without certain coachwork components. His basic theme takes influence from Gordon Buehrig's Auburn 851, very much of-mind as the Cord empire has lately allowed one to run at Bonneville. But the Model J platform is bigger, requiring a more dynamic, forceful hand.

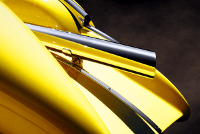

More typical of an LSR in miniature, Herb Newport narrowed the body, wide enough to contain two seats but mean enough to produce a slender fuselage between the wheels. Cowls at the front channel air along the flanks. When run at Bonneville, the team removed the skirted fenders, but used the nacelles aft of the front tyres and both fore and aft of the rear tyres to reduce turbulence. The car also uses full underbody skirts to smooth airflow beneath. The headrest fairings are part of the original record design, though Jenkins removed them during the car's Curtiss-powered incarnation.

Variations: Tracking Duesenberg J-557 through the Years

Original: The Duesenberg Special (retroactively Mormon Meteor) runs at Bonneville as described above. Break points between all aspects of the variants described below may not be exact, but we see evidence of these particular incarnations in period photos.

Variation 1: When Ab Jenkins swaps J-557 for Curtiss Conqueror V-12 power, he removes the headrest fairings and installs a tall fin on the rear deck. Contrasting contemporary flair for graceful curves, the fin looks reminiscent of today's Le Mans prototype cars—purely functional, and not quite pretty. He christens the car the "Mormon Meteor," which eventually applies retroactively to the Duesenberg Special. So this version of the car becomes known as the Mormon Meteor II, which for all intents and purposes ceases to exist when Jenkins removes the Curtiss motor and replaces Lycoming J-557 in the chassis.

Variation 2: After he retires the car from Bonneville with the original J-557 motor, Jenkins removes the giant fin. He does not replace the headrest fairings, but adds fenders, completing the fully closed, pod-like look we see today. A windscreen reemerges, and Jenkins cuts simple, though not inelegant doors into the body. The exhaust routes in an angular 'U' shape below the cockpit along the right flank, granting space for the passenger door to open. Nifty bumpers appear, the front unit including a central ring to frame the monocle headlamp. Now part of the car's lore, both sides of the bonnet receive a 'Mormon Meteor' insignia where the chromed 'Duesenberg' lettering had been, effectively writing over the original Duesenberg Special moniker. For practicality, Jenkins mounts a spare wheel and tyre kit on the left flank. In this configuration, and particularly from the left, the Mormon Meteor looks a bit like a melted and mutated Auburn 851 Speedster.

Variation 3: By the mid 1940s, the car becomes deep candy-apple red and loses its 'Mormon Meteor' bonnet signage. The side-mount spare remains, as do the ornamental bumpers. Wire wheels remain, while white walls come and go. A trio of small headlights supplement the one, large lamp below the grille.

Variation 4: At this point, J-557 begins to gravitate back toward to its original form—less the road car, better appreciated for its record-breaking history. The car returns to its finch yellow paint and regains traditional black tyres with red wire wheels. The spare remains on the left flank and the U-shaped exhaust route on the right. Headrest fairings are still absent, but a larger pair of headlamps replace the small trio. Around this time, the chrome 'Duesenberg' lettering reappears on the bonnet, along with the chrome 'Ab Jenkins' signature.

J-557 Today: The Duesenberg Mormon Meteor Restored by Harry Yeaggy

When Harry Yeaggy purchased the car in 2004, he gave J-557 a complete restoration. The point of presentation today can best be placed as the time when J-557 crossed over from being a speed record car to David Abbott Jenkins' personal car; it isn't perfectly one or the other, but perhaps the best combination of both. Like the record version, the exhaust is a straight unit and the body uses simple cut-down curves in lieu of doors; it is almost the Duesenberg Special, but perhaps a roadworthy expression as Herb Newport envisaged.

All of the bumpers and lights are gone, but the fully formed fenders join the nacelles, which rather helps pull the design together into one cohesive theme. J-557 finally gained newly fabricated headrest fairings for the rear deck, complement to the streamlined running gear and aerodynamic underbody fairings.

As it is, J-557 evokes the spirit of classic era speed record cars—long lines and big curves doing their best to hide the bulk required to contain high-horsepower engineering. There are many strange intricacies in the bodywork: the smooth bonnet bulge over the supercharger, integrated steps inside the rear fenders, and staggered, asymmetric seats complemented by those separate, off-kilter headrest fairings. In aggregate, these features are nothing short of wonderful, placing the Mormon Meteor in league with the Stout Scarab and original Pierce-Arrow Silver Arrow in terms of designs that spread innovative aerodynamic thinking across a broad canvas.

Xenia Comparison: Duesenberg J-557 Compared to the Hispano-Suiza H6B Dubonnet Xenia

For pure design impact, J-557 looks a bit like the open cousin of Jacques Saoutchik's Hispano-Suiza H6B Dubonnet Xenia Coupe of 1938. The two designs share a similar eruption of curve. Only the Duesenberg is no mere bombast, whereas the Xenia was built for show.

Linking the two together is no shortage of aeronautical thinking perpetuated by the accidental truth that shapes that look fast actually are. Duesenberg J-557 looks monstrously fast. The Xenia coupe looks fast in a futuristic sense, a bit of science-fiction. But because they are both designed with similar aerodynamic principles and built on super engineering, they both represent the same sense of excitement despite very different origin stories.

A glance below the tail of each suggests common ancestry, pointed sweeps and fairings for underbody airflow. The Xenia echoes Georges Paulin in its angular finesse, determinately French, but the wingtip treatment of the back deck on both designs makes them jet-age oracles.

Spaced apart by three years, we find in Newport's J-557 an early example of shapes that will emerge with greater popularity in Europe. This sequence is similar to Phillip Wright's Silver Arrow, where these early American designs are experimental in nature, and not followed up with any credible attempt to broaden their influence. Duesenberg meant for the Special to be a pleasing automobile, but the American public tilted toward the conservative when new design ideas emerged.

Last Updated: Mar 26, 2025