Prologue:

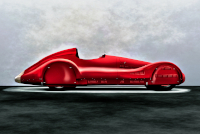

The 4-cylinder Maserati develop at the close of the decade advances high-output, small-capacity technology well beyond that of its modest 4CS ancestors. Perhaps the ultimate configuration, this streamlined 4CL takes aim at one marquee event, the 1939 Gran Premio di Tripoli.

Presumed to be chassis #1565, this unique streamliner has become a much asked-after curiosity owing to its disappearance. Maserati sleuths suggest the car received a conventional monoposto body following the Tripoli race, and that the coachwork yet survived at the Maserati factory into the post-War era. But today, neither chassis nor coachwork exist, the artefacts scattered and lost, our appetite for the car's aerodynamic shape whetted only by the colorless granularity of old media.

My interest involves the story, for sure, but also the opportunity to provide deeper and more delicate visual support than known from period monochrome photographs and small-scale models.

In this respect, I should first commend Mr. Shaun Collins, who in late 2016 published a 3D model of this car online. Modeling a design so curvaceous using triangular polygons is far more difficult than drawing a flat image. Despite the difficulty, his sculpting of the tail is quite good.

But the upshot is that I can use his model to test perspectives of the car. By cross-referencing period photographs, I can then illustrate a selected pose. The results are perspectives selected for their intrinsic merit, as opposed to building upon poses taken from my stock, which might look decent in end, but would be based on convenience as much as preference. In this case, with the perspectives settled I can focus on sculpting the correct form, painting the contours, and filling in the details.

Hopefully, those who have long sought a detailed look at this car will find reward in this profile. Chassis #1565 is an important piece of the Maserati story, and a meaningful answer to the question of what I can contribute to the classic motorcar discussion that folks might not have seen.

- - - - - - - - - -

► Image Source: Native illustration files and Nikon D200 (10.2 MP)

Finished resolutions are: (1) 9.4 MP, (2) 8.0 MP, (3) 10.0 MP. Not the same high-resolution output as my previous lost Maserati illustrations, but the lower resolution eases the burden of depicting multiple perspectives.

References:

- Cancellieri, Gianni; Dal Monte, Luca; De Agostini, Cesare; Ramaciotti, Lorenzo. (English translation by Neil Davenport and Robert Newman.) "Maserati, A Century of History: The Official Book" Giorgio Nada Editore, Vimodrone, Milano, Italia. 2013, page 272

- Crump, Richard; de la Rive Box, Rob. "Maserati Sports, Racing and GT Cars from 1926" Third Edition, G.T. Foulis & Company for Haynes Publishing Group PLC, Somerset, England. 1992, page 80, 84, 88-89

- The Golden Era of Grand Prix Racing: "1939 Grand Prix Season, Part II, XIII° Gran Premio di Tripoli" by Leif Snellman

- Shaun Collins: Creator of the 3D model used to sample perspectives in these illustrations.

- UltimateCarPage: Source for Maserati 4CL specifications, by Wouter Melissen, December 13, 2004.

- Mercedes-AMG Petronas Formula One Team: Vintage footage of the 1939 Tripoli Grand Prix showing the W165 and 4CL at speed.

Gran Premio di Tripoli, 1939

The 1939 Tripoli Grand Prix is a peculiar moment in history. To begin with, the event comes into existence in 1925 to promote tourism in Italian Tripolitania (present-day Libya), with the more subversive purpose of urging colonization in that southern Mediterranean region. But the race, like the Italian colonial campaign, is a difficult sell for the public.

As with land holdings as far east as Eritrea, the oncoming war will nullify Italian aspirations of empire-building beyond the European continent. That said, the Tripoli Grand Prix struggles into the 1930s. Then in 1933 the government builds an 8.1-mile high-speed course around the Mellaha salt basin just off the Mediterranean coast. Mellaha Lake serves as a non-championship leg of the Grand Prix calendar through 1940.

Another feature of the Tripoli Grand Prix, (one of Italian proclivity), race organizers hold a lottery every year, giving cash prizes to tickets that correspond with the 30 race qualifiers. This anecdote is significant for the 1939 edition, which is a historical outlier.

Because of the lottery, race officials must turn out a field of 30 automobiles. To reach this quota, the Gran Premio di Tripoli has in previous years invited both voiturette and Grand Prix formula cars to compete together. In this format, the 1938 race suffers two fatalities due in part to the performance differential of the cars, which leads the organizers to stipulate that in 1939 Tripoli will run a 1.5-litre voiturette formula exclusively. Also influential in this decision is the perspective of technical resource rationing leading up to the war and the general atrophy of international competition, which places favor on small capacity race cars for the 1940 Grand Prix season in whatever form it might take.

These are the reasons Tripoli is an exclusive voiturette race in 1939. Many speak of Italian frustration over German racing dominance, suggesting that the change tilts the odds toward Alfa Romeo's class-leading 158 Alfetta, and that the Mercedes-Benz W165 is something of a surprise challenger. In reality, race organizers stay in communication with Mercedes-Benz over the readiness of the W165, which the factory develops in little more than eight months, just to make sure the Tripoli grid fields 30 cars.

Therefore, however much the 1939 Tripoli Grand Prix appears to be a ploy for Italian victory, the race depends somewhat on Mercedes' participation to keep Tripoli's numerology of '30' intact—30 cars, 30 laps, 30 lottery tickets.

So, as historian Leif Snellman writes, "the 1939 Tripoli race assembles the greatest field of voiturette cars ever; it includes six Alfettas, introduces the Maserati 4CL, and proves to be the only appearance of the Maserati 4CL streamliner."

Of this 4CL, Maserati's new car runs a DOHC supercharged unit, as expected, but with 4 valves per cylinder and (in this case) a fully faired streamlined body engineered by Stabilimenti Farina. Squeezing about 220 bhp out of 1½ litre, Luigi Villoresi takes pole position with a lap time of 3:41.8, averaging 131.875 mph.

Of course motorsport wonks know that Mercedes-Benz come through; they prepare a new car specifically for Tripoli, the 1.5-litre W165, and easily snag first and second with Hermann Lang and Rudolph Caracciola, respectively.

The key appears to be Mercedes' ability to handle extreme heat. Nearly all of the Italian machines suffer heat-related maladies. And on top of mechanical fatigue, Villoresi's streamliner poses a challenge rather common to closed coupe race cars. He comments before the race that the most one could stand inside the fully shrouded 4CL is a meager six laps, well short of the distance required.

No matter for Villoresi, because in the race he experiences trouble with the gearbox from the start, and by the end of lap one retires with piston failure.

Still, the works experiment is smart, using period aerodynamic theory not unlike the German's own high-speed machinations, which is more than Alfa Romeo ever wager in open-wheel competition. And the results are palpable, pole position over both Alfa and Mercedes. Only the reliability of the new 4-valve head in the North African desert brings Villoresi's cause to a quick halt. In this respect, pole position is the best result the 4CL streamliner can achieve.

Maserati 4CL Streamliner, #1565

We lose sight of the 4CL when considering the top voiturette cars of the classic era. The bespoke Mercedes-Benz W165 proves itself in Tripoli, and these are cars that survive today. The Alfa Romeo 158 Alfetta develops into the championship-winning 159, examples of which also survive today. But the Maserati 4CL, and in particular this ultimate specification that proves a hair faster than both of those cars in 1939, is not so revered.

Our interest is something of a curiosity over the design of this particular streamliner, whereas the 4CL designation misleads our expectations, recalling the modest origins of Maserati 4-cylinder sports cars. But the 4CL wins no fewer than ten races in its career, often with Luigi Villoresi and Tazio Nuvolari at the wheel. These wins including the 1940 Targa Florio with Villoresi, and a host of post-War victories in both France and Italy. For its performance quotient, the 4CL equals the W165 and Alfetta in potential, only that it isn't quite so romantic does it suffer disregard. And that the streamliner no longer exists, most distinct of its kind, further impairs our impression of the past.

To get into the business of the streamliner, chassis #1565 is perhaps a tubular 6CM 1500 or a tubular chassis similar to the 6CM. Crump and de la Rive Box place #1565 under both the 6CM 1500 and 4CL 1500 registers. They write: "Works car with aerodynamic body for Villoresi and 6CM frame, transferred into 6CM after the 1939 Tripoli GP." This account is consistent with the supposition that #1565 becomes a conventional monoposto after Tripoli. And if it were a 6CM, the car would be a works mount for Giovanni Rocco and Paul Pietsch. But this isn't to say that it is a 6CM, then a 4CL, and then a 6CM again, but rather a tubular chassis monoposto first of 4C and later 6C power.

In any case, the body is an aerodynamic development by Stabilimenti Farina. Prior to the Tripoli Grand Prix, Maserati test the car on the the Autostrada Firenze-Mare, site of Giuseppe Furmanik's speed record attempts, doing so in various configurations.

The streamliner first appears in primered alloy with a cowl along the upper edge of the intake and wheel skirts front and rear. By the time the car arrives in Tripoli, now painted red, Maserati do away with the intake cowl and rear wheel skirts.

We can see the car wearing #38 in vintage footage from Tripoli, where the streamlined body is easy to spot. The 4CL's appearance is an extreme case of experimental coachwork in motorsport—much like the Auto Union and Mercedes-Benz Avus streamliners—yet a rare instance applied to voiturettes. At this point in history, the trade-off seems fair. Shrouds increase top-end speed. But, to say nothing of road-holding concessions, engineers don't quite know how to keep a closed body adequately cool over race distance. The concept is theoretically superior, difficult to perfect, and under the torrid conditions of Tripoli, simply impractical.

Motor: 1,491 cc, cast-iron block and head | 78 mm x 78 mm | 6.5:1 compression | #1564

Valvetrain: DOHC, 4 valves per cylinder

Aspiration: Weber 45 DCO carburetor, Roots-type supercharger

Power: 220 bhp at 8,000 rpm

Drivetrain: 4-speed gearbox, rear-wheel drive

Front Suspension: independent double-wishbones, torsion bars, Houdaille friction dampers

Rear Suspension: live axle, semi-elliptic leaf springs, Houdaille friction dampers

Architecture: tubular steel frame with aluminum coachwork by Stabilimenti Farina of Torino

Wheelbase: 2,500 mm (98.4 inches)

If the 4CL streamliner chassis were identical to a 6CM 1500, then the wheelbase would be 2,490 mm, an academic difference.

Top Speed: 250 km/h (155.3 mph)

Crump and de la Rive Box suggest 250 km/h for a standard 4CL 1500. The 131.875 figure cited in this profile is an average speed recorded over one 8.165-mile lap of the Mellaha Lake circuit in Tripoli. To compete against the Mercedes-Benz W165 and claim pole position on a high-speed circuit would require a car capable of speeds in the 155 mph neighborhood. With an aerodynamic body, this 4CL would add a bit of weight but gain an advantage in top speed, so the 250 km/h estimate is at least reasonable.

Etymology:

The '4CL' designation indicates a 4-cylinder development on a long chassis, 2,500 mm to the 2,400 mm of the 4CM. I use the term, 'aerodinamica' to indicate the streamlined coachwork by Stabilimenti Farina.

We presume this car is chassis #1565, which is something of a tubular frame special similar or identical to the 6CM 1500.

Figures:

Maserati build 26 of the 4CL 1500. Of these, #1565 is unique. Neither the chassis nor its coachwork survive.

Crump and de la Rive Box suggest that the motor in this streamliner is #1564, which is a works car for Count Trossi, Franco Cortese, and Luigi Villoresi. Chassis #1564 does survive; I cannot confirm whether it retains its original motor.

Land Shark: Observations on the 4CL Streamliner Design

After drawing a few perspectives and pouring over old photographs, I offer the following thoughts: The bonnet ventures out from the cockpit a short distance, then shunks downward on a sharp slope. The nose is rather long, longer than perceived in front quarter perspectives, the effect of which is diminished by the integral front valance.

A pizza-oven intake returns from Giuseppe Furmanik's Siluro 4CM Carenato, but with better proportions for the shape of the nose. Menial inlets feed the front brakes, and a heavy complement of louvres on the front wheelskirts seems to be a rather hopeful measure to expel the resulting heat.

The front wheelskirts are not flat, but curl with the top-edge curvature of the front shrouds. The back edges of the skirts form a slight bulge where the fairings reach their widest point before sweeping inward toward the exhaust.

Louvres below the bonnet and along the front quarters seem perhaps too tightly configured, too narrow, and too few to provide adequate cooling. With the exhaust taken out wide to the left flank, and with so much clean sheet metal surrounding the cockpit, one can see the source of Villoresi's six-lap maximum race tolerance.

The coachwork appears designed to funnel heat from the mechanicals into the cockpit, with little isolation of the driver underneath the alloy drapery. Farina engineers likely considered external air flow at the expense of internal air flow, and it would be interesting to review German streamliners to understand how the cockpit is isolated from internal heat, if at all, or subsequently cooled.

The rockers carry fine sets of louvres and a rear vent fitted low, near the rear arch. The rear arches are lovely spherical forms, narrow, with elegant curvature through the rear wheelskirts. In quarter perspective, the flanks tuck in trim to the hips, (they are not linear), though I wonder whether Maserati altered the shape during the car's test development by reducing the inward-outward undulation. In any case, there is more four-part fender realization in the design than depictions often represent.

The headrest fairing is intriguing, in some period photographs forming two compound forms and in some photographs three, owing to the contours above the driver's shoulders.

The tail sweeps down into a rearward proboscis, all tangents smoothing out elegantly. Two final sets of louvres lie mostly flat on the coachwork and curve toward the point, but these are so far aft of any heat source that it's tempting to suggest they are notional more than functional. On the other hand, these louvres may serve to prevent drag from accumulating from air trapped inside the tail.

As a general impression, the shape reminds me of a sand tiger shark. I realize this reference could target any number of sharks depending on one's geography, so what I really mean is Carcharias taurus, which is the shark you probably know from your local aquarium. The shape is sleek yet also bulbous, with a high dorsal arc. The nose and mouth are conversely low, and the tail elongated with multiple fins and contours.

Whether we describe the shark or the car, the design is slightly awkward but also powerful, a shape so clearly purposeful but not without a touch of oddity. Capturing that shape with any sense of fidelity is no easy trick, the alloy appearing fluid from one perspective to the next. But I've enjoyed the trouble and feel closer to the story than I might have if only reviewing the design from a distance.

Last Updated: May 20, 2025