Location:

Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum Demo Day, 2023

Owner: Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Prologue:

Profiling the 8C 2900B Mille Miglia became an epic feat of journalism when Simon Moore first coined "The Immortal Alfa Romeo Two-Nine" title in the 1970s. His work that followed in the next two decades codified the 2.9's status as the apogee of classic sports car romanticism. If Bugatti were kinetic art works to be objectified, classified for their beauty and eccentricity, then the Alfas were the muses to fall in love with, adored for their supercharged breath and voluptuous shape. The 8C 2900B and Type 57 SC both occupy the upper echelon of reverie. But if we are to believe historians and pundits alike, the Alfa stirs infatuation like a teenage heartthrob, all passion and race—none of that charming quirk that makes Bugatti cars so mesmerizing (and also undeniably French), just pure go-for-it curves.

And so we embark on a paean to illuminate the sin so many others have already committed, that the 8C 2900B MM is so obliteratingly loved that we forget its technical limits, forgive its narrow window of success, and reach for praise better suited to the loves who share our beds than a mere piece of machinery.

In this pursuit, we visited the 1938 Mille Miglia winner at a Simeone demo day one October afternoon. I kept my tripod in the car, for better or worse, because I did not want to impose on others and get in the way or create a fuss. So I'm living with a bit of fuzzy frustration in some shots, and my best portrait composition from the session is unusable. (I needed to work heartbreak into this story somehow.) In text, I've collected a number of sources beginning with Simon Moore, short of splurging on an original copy of his 1986 tome, and organized the data according to our thorough template. I hope the results provide enough to satisfy the devotion (lust?) that this car provokes among the smitten.

- - - - - - - - - -

► Image Source: Nikon D750 (24.3 MP)

References:

- Automobile Quarterly, Volume 11, Number 2, Second Quarter 1973, "The Immortal Alfa Romeo Two-Nine" by Peter Hull and Simon Moore, The Kutztown Publishing Company, Inc., Kutztown, PA, page 180-184, 187

- Automobile Quarterly, Volume 11, Number 2, Second Quarter 1973, "Living Legends: Alfa Romeo 8C 2900 B Mille Miglia" Automobile Quarterly Contributing Editors, The Kutztown Publishing Company, Inc., Kutztown, PA, page 188-195

- Automobile Quarterly, Volume 7, Number 2, Autumn 1963, "Mille Miglia! The Ultimate Road Race" by Don Vorderman, The Kutztown Publishing Company, Inc., Kutztown, PA, page 173

- Classic & Sports Car: April 2007, "On Cloud Two Nine" by Mick Walsh: Ralph Lauren's 1938 8C 2900-B Mille Miglia Touring Spider #412030, page 194-195, 197

- Moore, Simon. "The Immortal 2.9: Alfa Romeo 8C2900, Revised Edition" Parkside Publications, Inc., Seattle, WA. 2008, pages 303-315, 444, 461, 462, and others

- Simeone Foundation Auto Museum: Fred Simeone's own account of #412031, which corroborates the stories collected by Simon Moore and Automobile Quarterly, with greater description of the car's restoration.

- UltimateCarPage: The entry for chassis #412030, the Carlo Pintacuda car that lately became part of Ralph Lauren's collection, supplements our technical information. This piece includes Wouter Melissen's six rather definitive survey photos from the Pebble Beach Concours in 2005.

- UltimateCarPage: The entry for the Tipo 308C provides technical information on the Tipo C motor fitted to chassis #412031, by Wouter Melissen, March 26, 2007.

- SportsCarDigest: Home of the former Dennis David GP History catalogue, with story and photos from the 1938 Mille Miglia.

- RacingSportsCars: Full 1938 Mille Miglia entrants and results.

The late Dr. Frederick Simeone acquired his 8C 2900B Mille Miglia Touring Spider around 1980—early, he explains, in his classic car odyssey. He spends some time discussing the merits of #412031 as the fastest road car of the classic era, owing to the exploits of Hugh Hunter, the Englishman who bought the car from Alfa Romeo at the 1938 London Motor show. In the moment, Alfa displayed the car as the 1938 Mille Miglia winner and intended not to sell #412031 if not for Hunter's exuberant checkbook. Hunter then took the Mille Miglia Touring Spider to race at Brooklands.

Simeone describes the stage-type competition of Brooklands' Fastest Road Car contest, an iteration of which his Castagna-bodied 8C 2300 Mille Miglia entered a few years prior, and also the plaudits of Dennis May, who reported on the event for The Autocar. No doubt, this particular Mille Miglia spider was the fastest car at Brooklands in 1938, the only one of its stable powered by the Tipo 308 Grand Prix motor. But of the day, the closed 8C 2900B Le Mans Berlinetta might be faster still owing to its aerodynamics, despite the horsepower deficit.

So too, the closest competition for the 8C 2900B Mille Miglia would be the Delahaye 145 with its lightweight body and new V-12, (as opposed to the Delahaye 135 that appeared at Brooklands).

But this race had already been run, not in the abstract but in the thousand-mile proving ground that was the 1938 Mille Miglia, and it was won by the Alfa Romeo. Excepting the Delahaye's poor luck, Biondetti and Pintacuda proved the 8C's speed on fast runs between Italian cities. So the Brooklands contest settled very little.

If one were to test the fastest road cars of the classic era, (meaning a road-worthy sports-racing car), then we would require this 8C 2900B Mille Miglia Touring Spider with its Tipo 308 motor, the 8C 2900B Le Mans Touring Berlinetta with its aerodynamic body, a Delahaye 145, and also a Duesenberg SSJ, (if not the SJ Mormon Meteor that actually set land speed records). A little thought experiment, for sure.

Just note that these cars are not German laboratory experiments but still-practical examples of classic era machinery. Italian, French, or American, the fastest car offered from each country could take to a public road and run at speed for hours. And in the flesh, their skin and their sound passed by so many people as to capture the imagination. The Alfa Romeo is the romantic of the bunch—the red car, the one capable of eliciting passion in its curves and supercharged purr.

What we see here is that 1938 Mille Miglia winner with Tipo 308 Grand Prix motor, same of Hugh Hunter and the Brooklands contest, owned and restored and occasionally exercised by the Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum. Many thanks go to the Simeone Foundation for making artefacts like this Alfa Romeo so accessible. The accounts below discuss the car's Mille Miglia history and later restoration.

Clemente Biondetti, Carlo Pintacuda, and the 1938 Mille Miglia

The 1938 Mille Miglia story is as much about Pintacuda and the second place car (#412030) as Biondetti and the winning car depicted here (#412031). By the 1938 edition, Carlo Maria Pintacuda has won the Mille Miglia twice, carving out the characterisation of a race favorite. He reprises his 1938 drive with mechanic Paride Mambelli, same of his 1937 victory.

Alfa Romeo prepares four 8C cars for the Mille Miglia, managed this year by Enzo Ferrari, though not under the Scuderia Ferrari banner as in years past, but rather as a factory works team, Alfa Corse. This organizational change marks the shift that will soon urge Ferrari to become an independent manufacturer. Engineer extradordinaire Vittorio Jano has already departed, and will of course reconnect with Ferrari in the post-War era.

The main challenge to Alfa Romeo arrives from France in the form of the 4.5 litre V-12 Delahaye 145, driven by René Dreyfus. 1938 is Delahaye's best opportunity to steal Mille Miglia victory from the Italians, fielding their own Grand Prix derived car of comparable power and speed. The 145 matches 8C 2900B specifications with naturally aspirated big displacement and exotic alloy, creating a fast, lightweight racing car. Robert "René" Mazaud also joins the Delahaye cause in the more docile 135 CS. A stable of BMW 328s and the usual cadre of private Alfa Romeo entries round out the field of 140 cars, with a start time of 02:00 in Brescia.

Between Biondetti and Pintacuda, the former receives the sole 8C 2900B with a 308C Grand Prix motor, providing a sizable horsepower advantage. But Pintacuda's prowess on the road remains unmatched. He sets a new record to Bologna averaging 112 mph, arriving two minutes ahead of Dreyfus who runs 20 seconds ahead of Biondetti, He averages 130.8 mph on the road to Rome. At this point, Biondetti runs second with Dreyfus scuppered by a stone that punches through his radiator while passing a slower car. But the gap to Pintacuda is now four minutes and growing.

Heading back north through Terni, Pintacuda's brakes seize and Mambelli needs at least 14 minutes to free them and get the duo back on the road. Biondetti and mechanic Aldo Stefani overtake, building a lead that should solidify victory. But Pintacuda, feeling himself, pulls back nearly all of that gap. He and Mambelli cross the finish line in Brescia 2:02 behind the car of Biondetti and Stefani. But of course in the starting order, Biondetti had left Brescia two minutes before Pintacuda, so Carlo missed his third victory by just two seconds after 1,005.2 miles of racing.

Third place falls to Piero Dusio and mechanic Rolando Boninsegni in an 8C 2900A, the model that won the previous two editions.

With Dreyfus and his mechanic Maurice Varet foiled by their punctured radiator, they finish fourth. And there will be no chance for the Delahaye 145 to reprise, as France withdraw their support for motor racing in Italy the following year in objection to the war.

Fifth place lands in the lap of René Auguste Joseph Carrière, the former Delahaye works driver in his lone season driving for Talbot-Lago Darracq. He drives a 4½ litre T150-C with his mechanic Jacques van der Pijl.

Another Alfa Romeo places sixth, this an aged 1932 8C 2300 Monza piloted by Ludovico and Alessando Wild, who race under the pseudonyms "Ventidue" (twenty-two) and "Ventuno" (twenty-one).

Mazaud and mechanic Julio Quinlin bring the Delahaye 135 home in seventh place before the 2-litre BMW 328 entrants trickle in.

As to the other two 8C 2900B Mille Miglia Touring Spiders run by Alfa Corse, Nino Farina and Stefano Meazza have crashed out. And the car shared by Mimi Villoresi and Eugenio Siena has suffered a blown motor while Siena was driving. After the Mille Miglia, Alfa Romeo rebuild both cars, which survive today as racing specials.

Among the most closely contested Mille Miglia events, 1938 also marks one of the terrific auto-racing massacres. AQ note that "late in the afternoon... a Lancia Aprilia lost control on the streets of Bologna, plowing into the crowd and killing ten persons (seven of whom were children) and hospitalizing 23 more. There was such a tremendous public outcry over this tragedy that the race was cancelled for the following year."

The 8C 2900B Mille Miglia in the Hugh Hunter Era

Following the 1938 Mille Miglia, Alfa Romeo send #412031 to the London Motor Show. Writing for the "The Autocar" in August 18, 1944, Denis May describes the scene: "When the Alfa people sent the Mille Miglia winner to London at the time of the 1938 Motor Show they bought it a return ticket, drilling the trustees to say "not for sale" in four languages and with chilling adamancy." However, these effort fall short of Hugh Hunter's check book.

After purchasing the car directly from Alfa Romeo at the London Motor Show in 1938, Hunter keeps #412031 through the war. He races the 8C through 1939, including a few British Automobile Racing Club events.

May further recounts, "Hugh Hunter chose the Alfa because he wanted a car that could be raced and blinded around the roads without the need for periodical rebuilds; a car, that is, whose makers had done their own experimental and development work rather than leave it to the customer. He packed twelve meetings—circuit races, speed trails, and hillclimbs—in the curtailed 1939 season, topping up with some 4,500 miles on the road. No one could accuse him of sparing the horses, but breakages were nil."

The accounts of Simon Moore and Fred Simeone diverge at this stage, because Moore claims that Hunter runs this 8C 2900B MM Touring Spider at the 1939 Brooklands fastest sports car content, whereas Simeone states that Guy Templar runs a Castagna-bodied 8C 2300 MM Spider, chassis #2211072. Oddly enough, the Simeone foundation owns both cars. Perhaps both cars compete, though Denis May, who claims to have been a spectator in 1939, references Hunter and the 8C 2900.

In any case, Moore recites a hefty supply of notes from the Hunter era, including a yet older article from "The Autocar" by John Dugdale on roadgoing impressions of the 8C. The most salient description reads, "To obtain the maximum performance—which is naturally the object of Alfa Romeo drivers—the best plan is to make full use of the gears. This was shown me to advantage as, with the cold wind nagging around the windscreen at my cheek, we accelerated to 65 mph in second, 90 mph in third, and to 110 mph (4,500 rpm) in top on the Denham by-pass past London Film Productions' Studios. The car was still accelerating when Hunter braked for the gradual curve which followed, and it was only then that I realized our speed, for we came into that gentle curve so fast that it looked like a nasty corner."

In 1945, Hunter sells #412031 to Tony Crook (Thomas Anthony Donald Crook), an avid racer who just scratched the Grand Prix ranks and later allied with Bristol Cars. Moore notes, "Tony Crook lightened the car by fitting cycle wings front and back for competition events. He made a new tail but retained the original one." With some regret, in December of 1951 Crook sells #412031 to Major E.J. Thomson of Scotland.

Thomson runs the car con gusto, intermittently removing and refitting the running gear. However, the skirts become lost to the ages before #412031 reaches auction in 1970, where it uses diminutive cycle fenders. Simeone writes, "It is interesting to note that although the car had been seen wingless in various photographs in the late 1940s, in pictures taken in the 1950s the original fenders were refitted. They never changed the rest of the body over the gas tank. I’ve always wondered what happened to these fenders which apparently could come off and on at will, but an attempt to discover them by a fellow car collector’s visit to the Thomson estate was fruitless."

Dr. Simeone and the 8C 2900B Mille Miglia Restoration

Bill Serri buys #412031 from the Scots auction and brings the car to the US. Restoration begins with the help of Phil Hill's Santa Monica workshop. Excellent circumstances these, because Hill previously owned #412030 (Pintacuda's car) and had long been known for racing -030 in California, (to say nothing of his Formula 1 World Championship with Ferrari). In 1975, Hill commissions a motor rebuild using the original block, head, crank, and superchargers. He also sequesters #412030 from its then-owner, industrial designer Brooks Stevens, to help sort the coachwork on #412031.

Comparing the two, the Pintacuda car retains its original running gear but not its original body and underbelly for the nose, whereas the Biondetti car is rather the reverse. Chassis #412031 is original save for the running gear lost in Scotland.

With work halted at this point, Dr. Simeone purchases #412031 from Serri. But to complete the coachwork, Simeone opts not to copy the running gear of #412030 as Hill expects to do. Instead, considering the individual character of each hand-built 8C, Simeone and marque specialist Simon Moore dig through more research; eventually, they decide to use period photographs as guides for the running gear.

Back in the east, Alan Kirk of Pittsburgh crafts new fenders from the photographs, work Dr. Simeone writes about with effusive praise. He considers fidelity to the particular shape of the body an intrinsic quality of #412031, the true nature of Biondetti's car, as opposed to a mock based on Pintacuda's.

Simeone finally enlists David L. George to complete the restoration, ready in time for the 1986 Mille Miglia retrospective.

Dr. Simeone's 8C 2900 remains in beautiful driving condition. Unlike #412030—that of Phil Hill, Brooks Stevens, and Ralph Lauren ownership—the Biondetti 8C is not a concours car. The supercharger churns up a loud whisper and the exhaust taps out a quick snare drum rhythm; it appears a well planted car with a presence larger than its actual proportions, owing to its large wheels and low fenders. The effect is altogether modern, one of a few classic era cars that moves and sounds the way we expect of today's sports cars. Thankfully, the Simeone Foundation makes sure the public can still experience this thrill for themselves.

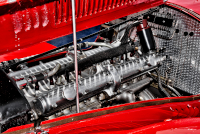

Motor: 2,991 cc (182.52 cubic inches) straight 8-cylinder, alloy block, fixed aluminum hemi-head | 69 mm x 100 mm | 6.1:1 compression

For the 1938 Mille Miglia, chassis #412031 runs a Tipo 308C Grand Prix motor, (#422025), a more powerful derivation of the 2.9, the other cars using a 2,905 cc motor developed from the 2900A. This car's identification plate reads, 'Tipo C' (not 'Tipo 8C 2900 B'), and those who have maintained the car find the cylinders of slightly larger bore, 69 mm to the 68 mm of the standard 2.9, against the same 100 mm stroke. Compression ratio increases from 5.8:1 to 6.1:1. The uprated motor gave Biondetti an edge in the 1938 race, though Pintacuda was such a Mille Miglia expert that he nearly won in spite of a 14-minute stop when his brakes fused.

When Hugh Hunter purchases the car, Alfa Romeo provide low and high-compression pistons, as well as a crown wheel and pinion set to change axle ratios. The low compression kit includes 5.75:1 pistons (like the standard 8C 2900B) and a 4.54:1 axle. As noted above, the Tipo 308 compression is 6.1:1 for racing, with a 4.16:1 axle. Hunter uses all the parts at his disposal, particularly the back end, changing the axle ratio from one meet to the next depending on the type of racing to be done. When running the high-compression head, he uses a mix of 50% pump discol, which itself is a petrol and alcohol blend, and 50% pure benzene.

Valvetrain: DOHC, 2 valves per cylinder, gear-driven via a central mechanism between each 4-cylinder block

Aspiration: twin Weber carburetors with twin Roots-type superchargers, each of which feeds one 4-cylinder block

Power: 295 bhp at 6,000 rpm

This figure represents the Tipo 308 motor in Grand Prix trim, which bests the standard 8C 2900 by about 70-75 brake horsepower, a striking figure from fewer than 3 litres in the classic era.

Drivetrain: 4-speed gearbox in transaxle rear-wheel drive layout

The gearbox runs in reverse compared to most modern units. A right-hand-drive car, gates for first and second gear are on the right, closer to the driver, so one rows backward toward the passenger. Moore, Walsh, and period racers note that the clutch is harsh, with long travel and a high take-up point. The rear transaxle also lags in the time required to warm, which is somewhat typical of the layout even today but might have seemed peculiar in period. Moore recollected in Automobile Quarterly that, "the gearbox, being in the back axle, took a long time to warm up and initially the gear lever was very stiff. Once the car was warmed up the performance was of the 'kick-in-the-back' variety and significantly better than that of the earlier 8C 2300 Alfas, with very effective brakes to go with it." Hull and Moore suggest that a cold gearbox explains why some 8C 2900B race starts were so poor, namely at Le Mans where Biondetti and Raymond Sommer shared the Touring Berlinetta. As to those brakes Moore mentioned, given that #412031 uses the more powerful Tipo 308 motor, the drums on this car also are slightly larger than on the other three Mille Miglia cars.

Front Suspension: independent double-wishbones with coil springs over hydraulic dampers

Rear Suspension: independent swing axle on transverse semi-elliptic leaf springs with radius arms for location and both hydraulic and friction dampers

Alfa derived this rear suspension set-up from the 1935-36 8C Grand Pix cars, transferred to the 2900A and carried over to the 2900B, as both use an advanced transaxle layout.

Architecture: steel ladder-frame chassis with Touring Superleggera aluminum coachwork, build #2139

For the frame, Moore notes that "the 1938 Mille Miglia cars on the 2.80m wheelbase have a frame that kicks down behind the differential instead of continuing back horizontally; this modification is the subject of a drawing dated January 17, 1938. However, it is not a complete chassis drawing, just the rear part. I suspect that the five Mille Miglia frames were modified from standard ones using a hacksaw and a welding torch."

On the coachwork, Touring's Carlo Felice Bianchi Anderloni developed the Superleggera process based on aircraft principles, creating a tubular space frame to which alloy panels are fixed using soft material spacers. The process floats the body without direct metal on metal contact, an approach often describes as hanging panels on the frame, though the technical term is 'swaging.' The Alfa Romeo 6C 2300B MM also uses this approach, among the first Superleggera exercises, and the Milanese coachbuilder will use the technique in the post-War era on a great many more marques and models.

Kerb Weight: 1,150 kg (2,535.3 lbs)

Wheelbase: 2,800 mm (110.2 inches)

Top Speed: 225 km/h (about 139.8 mph)

Classic & Sports Car cite 132 mph for the standard 8C 2900B MM, whereas Wouter Melissen at UltimateCarPage uses a round figure of 220 km/h (136.7) for the same standard car. Both figures pertain to chassis #412030. Chassis #412031 with the Tipo 308 motor is faster than its brethren. So this much is speculation, but adding a mere five kilometers per hour seems reasonable. As a Mille Miglia car, chassis #412031 did not run on a high-speed circuit as did the Le Mans Berlinetta, chassis #412033, and neither did it benefit from closed coupe aerodynamics. (The 8C 2900B Le Mans Touring Berlinetta is faster still owing to its closed aerodynamic body, despite running the standard 2,905 cc motor.) Our estimate accounts for a modest boost in speed, considering period driving conditions while acknowledging that no one will be so bold as to test this figure given the car's present-day value.

Etymology:

'8C 2900' refers to the motor, a straight 8-cylinder of 2.9 litre displacement. The 'B' designation refers to the second version of the 2900's development, which began in 1935, aimed directly at auto racing. 'Mille Miglia' refers to the car's preparation for the 1938 Mille Miglia. The term 'Touring Spider' echoes popular nomenclature for cars bodied by Touring of Milan using their Superleggera (Superlight) aluminum-on-tubular-frame system. Unlike the 2900A, which raced with cycle fenders and a Boticella fuselage, the 2900B raced as depicted, with full fenders and skirts.

Figures:

According to Peter Hull and Simon Moore, Alfa Romeo built four Mille Miglia Touring Spiders, though some sources cite five cars completed. The four original chassis begin with #412030, which is the 1938 Mille Miglia second-place car driven by Carlo Pintacuda and later owned by Phil Hill, Brooks Stevens, and Ralph Lauren. Next is this car, #412031, which is the 1938 Mille Miglia winner driven by Clemente Biondetti and owned by the Simeone Foundation. These top finishers are the only two cars of the original four that retain their Touring Superleggera coachwork, and their histories are almost certainly confirmed by Simon Moore.

The latter two Mille Migia cars pose a historical problem. The third 8C 2900B MM is #412032, which was likely driven by Emilio "Mimi" Villoresi and Eugenio Siena. Carlo Pintacuda crashed that car in testing after the Mille Miglia, and though heavily damaged, Alfa Romeo rebuilt it in 1940 as a cycle-fender special. Wartime would have shuttered production of new machinery, so repurposing a special race car, no matter how badly damaged, makes sense. Confusion persists about whether #412032 was not in fact Giuseppe "Nino" Farina's car for the 1938 race, owing to mis-matched license plates and duplicate race numbers applied to this and #412034 during scrutineering. In the 1973 Automobile Quarterly piece we cite here, Hull and Moore list #412032 as Farina's car, but Moore later clarified that identification had come from a contact in Milan, and that upon further research it seemed likely that #412032 is the Villoresi/Siena car.

So for the time being, #412034 seems to have been Farina's. That chassis also lost its original Touring coachwork, possibly as a result of incident in the post-War era, and today wears a cycle-fender special body similar to #412032. Both mystery chassis, #412032 and #412034, became part of the Schlumpf collection in Mulhouse, France.

The fifth car in this series is chassis #412033, which Touring bodied as a streamlined berlinetta for Le Mans. That rather famous car lives in Alfa Romeo's Museo Storico collection. Chassis #412033 is ostensibly the same as the Mille Miglia cars in technical specification, but not in preparation and certainly not in shape. Of course the chassis number sequence and basic drivetrain is probably why some sources cite five cars instead of four, whereas Alfa Romeo only prepared four for the 1938 Mille Miglia. The difference would read as four 8C 2900B MM Touring Spiders and one 8C 2900B LM Touring Berlinetta.

Roadster Quintessence: The Apogee of Classic Era Sports Cars

Achievement means less than appearance, perhaps more so as time distances the car from its achievements. Beauty beats history. Because if beautiful, then anyone can be taken in by a simple picture. History requires text and thought, even a broader understanding of context. And car people can be so boring.

So if we suggest that the 8C 2900B MM Touring Spider is the quintessential classic sports car, we would then waste words comparing worthy adversaries and nitpicking the peculiarities of different contexts on different continents.

In the end, the 8C is more qualifiably the ultimate classic era sports car. Among the fastest, the 8C 2900B MM is technically modern yet retains enough period design to straddle the then-and-now; it does what we expect of a modern sports car, and in some ways it really is while in other ways it clearly isn't. Dr. Simeone himself suggested the car is in fact a bridge, and technically this claim is true. Perhaps the Mercedes-Benz W196 to follow in the post-War era picks up on the other side of the divide.

More the case that we recognize the Italian flare for creating sports cars that are emotionally stirring. We trace the sports car lineage and supercar lineage alike through Italian automotive history and land upon the 8C 2900B MM as the ultra-example. In some sense, we label the 2900 the apogee by appearance alone and then work backward through texts and technical description to justify ourselves. We could draft criteria, but under the circumstance of rarity we understand that seeing the car in the flesh is so special as to prove the point. I can only try to convey that impression in these images.

Of the four prepared for the 1938 Mille Miglia, Biondetti's and Pintacuda's survive more or less intact. (This matter we discuss in the Production section.) We know these survivors today as the 8C of the Simeone Foundation (Biondetti) and that of Ralph Lauren (Pintacuda). The easy way to decode one from the other is of course that the Biondetti car wears red wire wheels, whereas the Pintacuda car wears chromed wire wheels. But there are of course many differences that we'll try to clarify, accepting that some judgments are still flimsy in the end.

Our aesthetics discussion is therefore largely comparative, whereas the design stems from Touring exercises and the preceding 8C 2900A Mille Miglia. Where that factory exercise is concerned, what we see in the 8C 2900B MM is what Touring meant the concept to be—again, the ultimate expression.

Decoding Roadsters: Comparing the 8C 2900B MM Touring Spiders of Dr. Simeone and Ralph Lauren

The two 8C 2900B Mille Miglia roadsters that survived the 20th century without major incident bear many differences; these are Simeone's #412031 depicted here (Biondetti), and Ralph Lauren's #412030 (Pintacuda). As discussed, Dr. Simeone and Simon Moore opted for an organic approach to fabricate new fenders for #412031 based on period photographs, rather than copy those that survived on #412030. Conversely, Simeone writes that much of the body on #412031 is original.

The fender difference is immediately noticeable in the fascia, where #412030 wears a horizontal valance that draws the outer fender edges into planar angles, as opposed to the curvature of #412031, whose valance instead sweeps gracefully within the fenders. For a shape so famously curvy, the linearity of #412030 fascia is surprising—less classic perhaps, but also indicative of aerodynamic trends and the transition toward 6C 2500 design exercises to follow in the next two years. In contrast, #412031 presents a wavy valance and prominent fenders that fit our conception of the quintessential classic era roadster.

Chassis #412030 had also lost its original belly cowl below the nose. When Automobile quarterly surveyed the Pintacuda car back in 1973—at the time, owned by Brooks Stevens—the underbody cowl was absent altogether, giving the car a toothy presence without any alloy to hold the lower part of the grille. The Pintacuda since car regained its cowl, but this unit is squared off, a wider dustbin shape that reaches the suspension arms. The bulbous belly tank piece fitted to #412031 is narrower and sits well within the suspension arms. From Simeone Foundation notes, this curved cowl might be original, though period photographs of the 1938 Mille Miglia support the shape of the cowl fitted to the Pintacuda car today.

Along the flank (eschewing the crescent vent configuration for the time being), chassis #412031 uses a separate body panel below the bonnet, whereas the body on #412030 is contiguous. The latter (Pintacuda's car) seems to be a refabrication, dating at least to the time #412030 was restored under Brooks Stevens. In the case of #412031, a straight panel line separates the bonnet and the bout below the bonnet from the rest of the body, the bout secured by rivets.

Working backward, the leading edge of the rear fenders on #412031 is fully contiguous alloy, whereas in this case #412030 displays a separate riveted surround for the three cooling slats. So the Pintacuda car uses contiguous sheet metal at the flank front under the bonnet, but a separate panel at the flank rear around the cooling slats. In contrast, the Biondetti car uses a separate bout panel at the flank front (perhaps original), and contiguous sheet metal at the flank rear around the cooling slats.

The shape of the tail fenders is also different. Today, Pintacuda's car sits slightly higher on the rear axle as the fenders sweep around the tail a bit more than on Biondetti's car. Here, on #412031, the rear fenders extend back a little more without the same degree of wrap, giving the car a longer appearance. Apart from differences in the fender lines, both cars use a ducktail back end that sits lower than the fenders, with an integrated spares compartment drawn into a fine point above the clasp.

On top of the deck, #412031 uses a tail light similar to most 8C 2900B road cars. For some time under Brooks Stevens' ownership, #412030 also used the same fixture, a practical concession, but under Ralph Lauren the car now does without—more in keeping with Mille Miglia preparation.

Crescent Cuts: Handwork on the 8C 2900B MM Touring Body

Along the right flank, the crescent and bar vents that cover the exhaust are slightly different in that #412031 adds an additional bar at the front, (nine bars and eight crescents). Dr. Simeone puzzled over the orientation of the fenders relative to these body cuts, and I find it difficult to understand exactly what the original state was relative to the restored version. Simeone writes that Alan Kirk pieced the refabricated fenders to the original body in the only way they could sit, accounting for period repairs to cooling vents and the original mounting slots.

The crescent vents below the bonnet are also different, with six on #412031 to the eight cuts on #412030, two more that run behind the bonnet clasps. Without a separate panel below the bonnet, #412030 adds much larger crescents. In either case, these vents demonstrate a hand-built approach; they are not well aligned and not particularly uniform in the graduation of their size. In contrast, the crescent exhaust cuts are much more uniform.

Contrary to the body, both bonnets appear to be fashioned identically. These panels opt for common louvres for intaking and expelling air, rather than the combination louvres and vents found on the 8C 2900A.

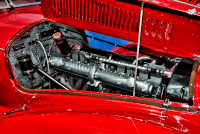

Bonnet Basics: Visuals of the Pintacuda 8C 2900B and Biondetti Tipo 308 Motors

Under the bonnet, the Pintacuda car wears antique cerulean paint on the block, a very similar color to 8C 2900B #412027. The Biondetti car here uses a bare unpainted block. So too, #412030 includes a bracket with four spare spark plugs, and the exhaust headers wear polished multicolor patina. In this case, the effect of the Pintacuda motor today is more concours d'elegance than race car, reminiscent of the luxury long-chassis cars sold to the public. The motor in #412031 is more like what we expect from a classic era racing car.

Of course, it is important to note that the motor in #412031 is a Tipo 308 Grand Prix unit, slightly more aggressive than even the race-prepared 2900. The two motors are very similar, differing slightly in the bore, and one would need to disassemble the units to uncover their peculiarities (none of which I can describe with any authority).

Cockpit Controls: Inside the 8C 2900B Mille Miglia

In retrospect, we look at the Veglia gauges as charming. But in period, some detractors considered the design more parts-bin and noted that the inset meters for fuel pressure and oil temperature could be difficult to read.

As mentioned, the gearbox gates are reversed, working from the driver outward to the passenger, and the pedal arrangement is the period Alfa type with center throttle. In this case, the throttle is less the button of the 6C 1750 and more a stubby metal bolt. The gearshift lever is a serpentine bar that requires the passenger (mechanic) to sit with skewed legs, affording space enough to work the box, as the gates themselves sit at the front right edge of the passenger seat.

But of course we the public expect idiosyncrasies from Italian sports cars. There cannot be anything so easy about the exotic.

Last Updated: Apr 19, 2025